Grampus Griseus

– Risso’s Dolphin –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[2] |

| Scientific classification |

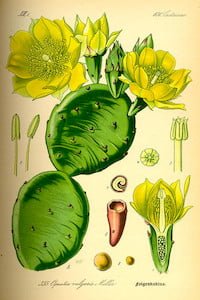

Grampus griseus (G. Cuvier, 1812)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Grampus Gray, 1828 [3] |

| Species: | G. griseus |

Risso’s dolphin (Grampus griseus) is the only species of dolphin in the genus Grampus. It is commonly known as the Monk dolphin among Taiwanese fishermen. Some of the closest related species to these dolphins include: pilot whales (Globicephala spp.), pygmy killer whales (Feresa attenuata), melon-headed whales (Peponocephala electra), and false killer whales (Pseudorca crassidens).[4]

Description

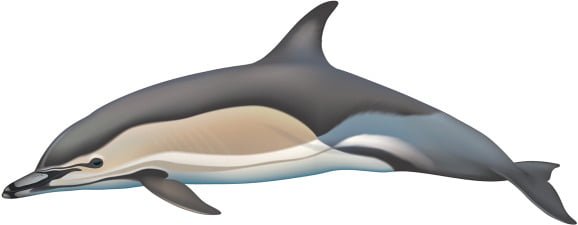

Risso’s dolphin has a relatively large anterior body and dorsal fin, while the posterior tapers to a relatively narrow tail. The bulbous head has a vertical crease in front.[5]

Infants are dorsally grey to brown and ventrally cream-colored, with a white anchor-shaped area between the pectorals and around the mouth. In older calves, the nonwhite areas darken to nearly black, and then lighten (except for the always dark dorsal fin). Linear scars mostly from social interaction eventually cover the bulk of the body; scarring is a common feature in toothed whales, but Risso’s dolphin tend to be unusually heavily scarred.[6] Older individuals appear mostly white. Most individuals have two to seven pairs of teeth, all in the lower jaw.[5]

Length is typically 10 feet (3.0 m), although specimens may reach 13.12 feet (4.00 m).[7] Like most dolphins, males are typically slightly larger than females. This species weighs 300–500 kilograms (660–1,100 lb), making it the largest species called “dolphin”.[8][9]

It is a tapered animal at the back and rather robust at the front. It has an almost square head with a well-marked melon *, which precedes a broad chest. There is a fold or groove joining the forehead to the upper lip , characteristic of the species. The Risso’s dolphin does not have a rostrum * on the muzzle, but a beak, which is hardly discernible.

A single vent * is visible on the top of the skull.

Grampus griseus does not have teeth on the upper jaw, but three to seven pairs of teeth (six to fourteen teeth) line the tip of the lower jaw.

The color of the grampus changes throughout its life: pale gray at young (with, in newborn subjects, slight white traces due to the folds of its fetal position) then darker, the body of individuals becomes white over time. time.

This change in color is due to the multiple scars and scarifications streaking their body, accumulating over time and resulting from interactions between individuals.

Some nice round and very dark eyes can then distinguish the clear mass.

The swimming blades (pectoral fins of cetaceans), in the shape of a crescent, keep a gray color.

The dorsal fin of this dolphin is very special: sickle-shaped, pointed at its end, it is thin and, in proportion to the length of the body, it is the longest dorsal of all cetaceans, It is darker than the rest of the body and is located in the middle of the back of the ‘animal.

The caudal fin, also dark, has pointed tips, receding backwards, and a well-marked central notch.

Taxonomy

Risso’s dolphin is named after Antoine Risso, whose description formed the basis of the first public description of the animal, by Georges Cuvier, in 1812. Another common name for the Risso’s dolphin is grampus (also the species’ genus), although this common name was more often used for the orca. The etymology of the word “grampus” is unclear. It may be an agglomeration of the Latin grandis piscis or French grand poisson, both meaning big fish. The specific epithet griseus refers to the mottled (almost scarred) grey colour of its body.

Range and Habitat

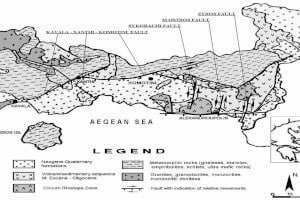

They are found worldwide in temperate and tropical waters, usually in deeper waters rather, but close to land. As well as the tropical parts of the Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, they are also found in the Persian Gulf and Mediterranean and Red Seas, but not the Black Sea (a stranding was recorded in the Sea of Marmara in 2012[10]). They range as far north as the Gulf of Alaska and southern Greenland and as far south as Tierra del Fuego.[5]

Biotope

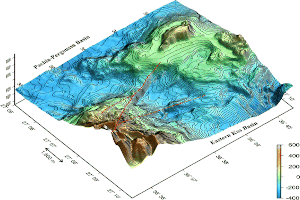

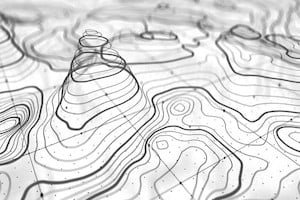

It is a deep-sea dolphin, sometimes approaching the coast, which frequents the continental slope, the plumb of drop offs, submarine canyons and funds reaching up to 1000 meters deep.

Their preferred environment is just off the continental shelf on steep banks, with water depths varying from 400–1,000 m (1,300–3,300 ft) and water temperatures at least 10 °C (50 °F) and preferably 15–20 °C (59–68 °F).[5]

The population around the continental shelf of the United States is estimated[by whom?] to be in excess of 60,000. In the Pacific, a census[which?] recorded 175,000 individuals in eastern tropical waters and 85,000 in the west. No global estimate exists.

Ecology

Alimentation

They feed almost exclusively on neritic and oceanic squid, mostly nocturnally. Predation does not appear significant. Mass strandings are infrequent.[5] Analysis carried out on the stomach contents of stranded specimens in Scotland showed that the most important species preyed on in Scottish waters is the curled octopus.[11]

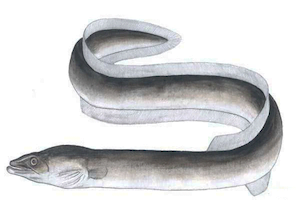

Most of the time the grampus is characterized as a teutophagous species, that is to say that it feeds almost exclusively on cephalopods and in particular on squid. It can also feed on small fish.

The palate of the animal is lined with protuberances of the gum that seem to act like false teeth. Its dentition distributed exclusively on the lower jaw (and it is the only species of its family in this case), is consistent with its diet.

Hunting is generally nocturnal (but this can vary) and his hunting technique makes extensive use of his echolocation system *. Risso’s dolphin can probe for up to 30 minutes to hunt.

Reproduction

Gestation requires an estimated 13–14 months, at intervals of 2-4 years. Calving reaches seasonal peaks in the winter in the eastern Pacific and in the summer and fall in the western Pacific. Females mature sexually at ages 8–10, and males at age 10–12. The oldest specimen reached 39.6 years.[5]

The calving period is quite uncertain, it is assumed to be quite flexible. Newborns have been observed in the Mediterranean both in May and July.

The color of young Grampus griseus is almost uniform olive gray to pale brown with a darker portion extending from the nape to the base of the caudal. It therefore does not show (yet) white scarifications.

Risso’s dolphins have successfully been taken into captivity in Japan and the United States, although not with the regularity of bottlenose dolphins or orcas. Hybrid Risso’s-bottlenose dolphins have been bred in captivity.

A population is found off Santa Catalina Island where they coexist with pilot whales to feed on the squid population. Although these species have not been seen to interact with each other, they take advantage of the commercial squid fishing that takes place at night. They have been seen by fishermen to feed around their boats.[12] They also travel with other cetaceans. They harass and surf the bow waves of gray whales, as well as ocean swells.[5]

Behavior

Social behavior

Risso’s dolphins do not require cutting teeth to process their cephalopod prey, which has allowed the species to evolve teeth as display weapons in mating conflicts.[6]

Risso’s dolphins have a stratified social organisation.[13] These dolphins typically travel in groups of between 10 and 51, but can sometimes form “super-pods” reaching up to a few thousand individuals. Smaller, stable subgroups exist within larger groups. These groups tend to be similar in age or sex.[14] Risso’s experience fidelity towards their groups. Long-term bonds are seen to correlate with adult males. Younger individuals experience less fidelity and can leave and join groups. Mothers show a high fidelity towards a group of mother and calves.[13] But, it is unclear whether or not these females stay together after their calves leave or remain in their natal pods.

Human interactions

Like other dolphins and marine animals, there have been documentations of these dolphins getting caught in seine-nets and gillnets across the globe.[4] Many of these incidents have resulted in death.[14] Small whaling operations have also been cause of some of these deaths. Pollution has also affected many individuals who have ingested plastic. Samples from these animals shows contamination within their tissue.[4]

In Ireland, though not apparently in England, Risso’s Dolphin was one of the royal fish which by virtue of the royal prerogative were the exclusive property of the English Crown.[15]

Conservation

The Risso’s dolphin populations of the North, Baltic, and Mediterranean Seas are listed on Appendix II[16] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), since they have an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements.[17]

In addition, Risso’s dolphin is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS),[18] the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS),[19] the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MoU)[20] and the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU).[21]

Risso’s dolphins are protected in the United States under the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1992. Currently, Japan, Indonesia, the Solomon Islands, and The Lesser Antilles hunt Risso’s dolphins.[14]

Strandings

At least one case report of strandings in Japan’s Goto Islands has been associated with parasitic neuropathy of the eighth cranial nerve by a trematode in the genus Nasitrema.[22] There was a recent reporting of a juvenile male Risso’s dolphin that was stranded alive on the coast of Gran Canaria on April 26, 2019. This was the first documented case of capture myopathy and stress cardiomyopathy in a male juvenile Risso’s dolphin that has received rehabilitation.[23]

Similar Species

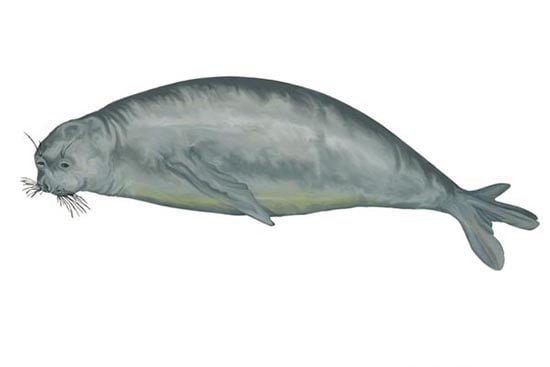

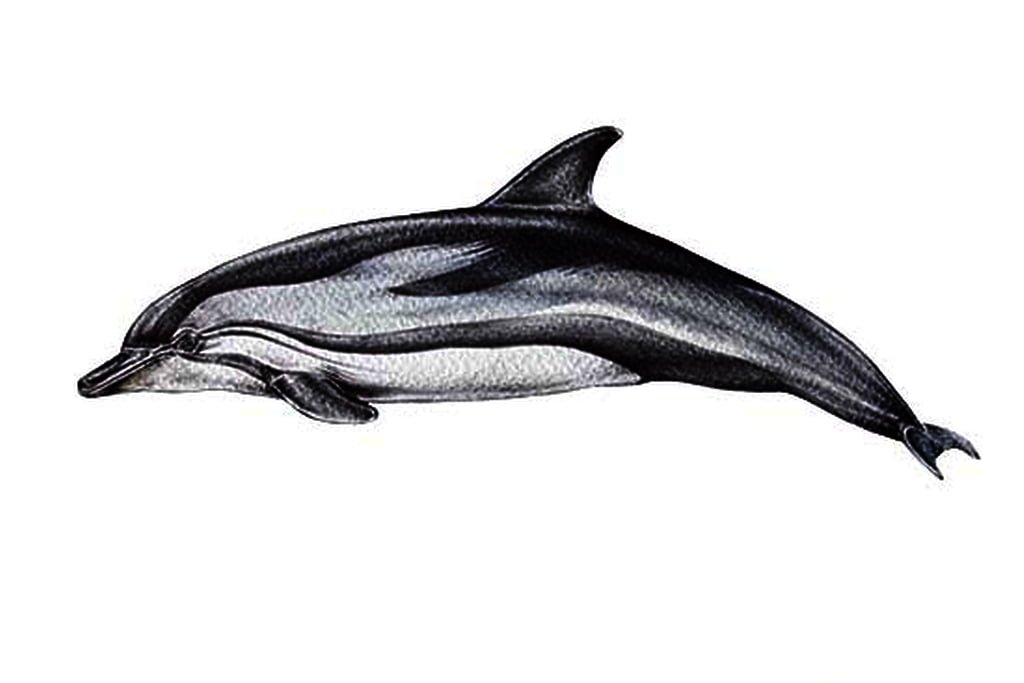

The differentiation between Risso’s dolphins and bottlenose dolphins (similar corpulences and similar ridge shapes) is easily done because the latter have a well demarcated rostrum and do not show the interlacing of scars fairly typical of Grampus griseus .

Pilot whales ( Globicephala melasand Globicephala macrorhynchus ) also have, like Grampus griseus , a head without rostrum, with a pronounced melon. They could therefore be a source of confusion with Risso’s dolphins, especially the youngest because of the dark color, because not scratched with clear, of the latter. But the shape of the dorsal fin is not at all the same and it falls backwards in pilot whales. In addition to the shape of this dorsal, the color differs in adult individuals of the two species: black for one and streaked with white for the other.

In fact, other cetacean species can still cause confusion with the young grampus, because of its dark color: peponocephalus, pseudo-killer whale or pygmy killer whale, for example. However, competitors in identification are generally darker and young Risso’s dolphins are usually found near adults of their species, which makes identification easier.

One could possibly confuse the old Risso’s dolphin with the beluga Delphinapterus leucas , because of the almost white color. But the belugas, which do not have a rostrum either, do not have the dorsal fin as high as in the grampus. In addition, they do not evolve in the same temperate waters and are often found further north.

From a distance, the tall dorsal fin of the Risso’s dolphin could possibly be mistaken for that of the male killer whale ( Orcinus orca ).

Associated Life

We can sometimes meet the Risso’s dolphin in the company of other species of dolphins: Tursiops truncatus , Stenella coeruleoalba , Delphinus delphis …

The exact reason for this fact, common in fact, for the mixing of species during certain activities remains to be determined.

Various Biology

The white scars found on Risso’s dolphin are due to the fact that the top layer of its epidermis does not renew itself. When it is scratched, it reveals a final white undercoat. These scars and scarifications can be the result of conflicting interactions or games between individuals but also and above all they are proof of a close relationship between these same individuals. Risso’s dolphin is a sociable animal that does not refrain from biting its congeners as “proofs of affection”.

Scars are also very useful for ketologists because they can allow them to recognize individuals among themselves during identification campaigns at sea.

Risso’s dolphin often adopts very specific postures. For example: the vertical body and the head out of the water for several seconds. This posture is called “spywatching” or “spy-hopping”.

It is also found vertical with the caudal fin in the air (“lobtailing”).

Jumps are rarer and often aborted. Relatively few jumps emerging from the entire body.

Grampus griseus swims slowly and calmly, the head and body emerging only partially, the large dorsal fin following the movement. He is nevertheless considered to be remarkably agile.

Sometimes, the caudal fin is visible when jumping, probing, or during social behavior.

The maximum speed of this cetacean is around 25-30 km / h (7-8 km / h at cruising speed, speed peaks at 30 km / h are rare).

His breath is rather short and quite difficult to observe from the surface.

Further Information

Risso’s dolphin sometimes groups together in schools of around ten individuals, but these groups can, by joining together, reach much larger sizes (sometimes several hundred, temporarily).

When hunting in groups, Risso’s dolphins often stand in line and sometimes mingle with groups of other species, notably the common dolphin but also bottlenose dolphins, blue and white dolphins, pilot whales, Dall’s porpoises, lagénorhynques Pacific white flanks, spotted dolphins , false killer whales, pygmy killer whales and even sperm whales and whales! Interaction with large mammals does not seem to scare them, on the contrary!

Inside a group of Grampus griseus, whatever the size of the group, it is possible that there is a particular social organization. For example, massive strandings led by their study to believe that subgroups comprising dolphins of the same age and the same sex were forming, even inside the school.

Risso’s dolphins are not migratory, but their behavior is somewhat reminiscent of nomadism. That is to say, they meet in the same places, with a periodicity of several months and return to these places regularly.

The population of Grampus griseus in the northwestern Mediterranean is estimated at around 3000 individuals but it is difficult to give an estimate of its population at the global level.

Some species of odontocetes in the Mediterranean are affected by a viral epidemic of morbillivirus, which has increased in recent years and is causing pneumonia and neurological disorders. While many blue and white dolphins Stenella coeruleoalba and bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus appear to be affected and run aground or die in the sea, it is not yet known whether Risso’s dolphin is really susceptible.

In New Zealand an individual named Pelorus-Jack escorted ships for 24 years (1888-1912) across the Cook Strait. This grampus was protected by law in 1904 after having been the object of an assassination attempt.

It is estimated that the longevity of Grampus griseus can exceed 40 years [Sidois 2008].

The main human-related dangers that Risso’s dolphin faces .

It happens that during fishing trips in the North Atlantic Risso’s dolphins are accidentally caught. On the other hand, they are part of the species knowingly hunted in Japan for consumption!

Like most cetacean species, our Risso’s dolphin is exposed to the risks of plastic bags and metal cans that it ingests. Many of these items were found in the autopsied stomachs of some stranded animals. Indeed, Grampus griseus seems to strongly appreciate the game with plastic bags which are the object of harsh “balloon” games between congeners and it is not surprising that ingestion occurs,

Antoine Risso (Nice pharmacist and naturalist) described this dolphin in 1811 for the first time from a specimen from Nice. Because he had no teeth at the top, like sperm whales, he called it Physetère (kind of membership and another common name for sperm whales ) and he sent a notice and a drawing to Georges Cuvier. In 1812, Cuvier found a specimen in Brest similar to that discovered a year earlier by Risso and could examine its skeleton. Cuvier will describe this species, will name it Delphinus griseus but in homage to his friend from Nice, Cuvier will give it the vernacular name of Risso’s dolphin.

On this subject, it was common, in the 18th-19th centuries, that simple members of learned societies, scholars who did not frequent the Parisian scientific circle but came from provincial academies (pharmacists, country doctors, lawyers, etc.) proof of an exemplary erudition by fixing meticulously observations and reflections on the spectacle of nature, often revealing themselves to be leading naturalists. In this regard, Cuvier holding Risso for one of the best naturalists of his time would have said of him “Ah, if only he had been Parisian!”.