Phocoena Phocoena

– Harbour Porpoise –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[3] |

Vulnerable (IUCN 3.1)[4] (Europe) |

| Scientific classification |

Phocoena phocoena (Linnaeus, 1758)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Phocoenidae |

| Genus: | Phocoena |

| Species: | P. phocoena |

The harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) is one of seven species of porpoise. It is one of the smallest marine mammals. As its name implies, it stays close to coastal areas or river estuaries, and as such, is the most familiar porpoise to whale watchers. This porpoise often ventures up rivers, and has been seen hundreds of miles from the sea. The harbour porpoise may be polytypic, with geographically distinct populations representing distinct races: P. p. phocoena in the North Atlantic and West Africa, P. p. relicta in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, an unnamed population in the northwestern Pacific and P. p. vomerina in the northeastern Pacific.[6]

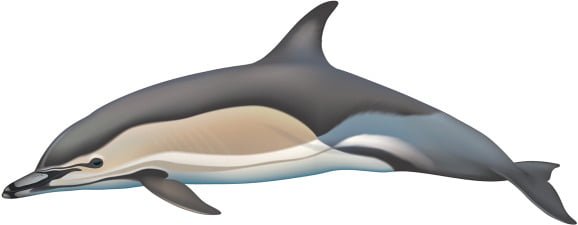

Description

The harbour porpoise is a little smaller than the other porpoises, at about 67–85 cm (26–33 in) long at birth, weighing 6.4–10 kg. Adults of both sexes grow to 1.4 to 1.9 m (4.6 to 6.2 ft). The females are heavier, with a maximum weight of around 76 kg (168 lb) compared with the males’ 61 kg (134 lb). The body is robust, and the animal is at its maximum girth just in front of its triangular dorsal fin. The beak is poorly demarcated.

The entire back , including the caudal peduncle, is dark gray . The boundary with the light sides is well defined, with sometimes gray spots in the front. The belly and throat are white. The porpoise’s head is broad, rounded, short and without a beak . A dark, inconspicuous line connects the mouth to the pectoral muscles.

The triangular dorsal fin is short, flat and at the base elongated. It is located practically in the center of the back. The pectorals are dark, small and rounded; they serve as a rudder. The design of the caudal has a central notch and outer tips. The sides are a slightly speckled, lighter grey. The underside is much whiter, though there are usually grey stripes running along the throat from the underside of the body.

The porpoise is very discreet on the surface when it comes up to breathe, but it is then spotted by the very regular and slow rhythm of the beautiful curves of its back. This casting swim is called “porpoising”. The breath is low and inconspicuous , but noisy. Its tail is never visible when it probes.

The female is slightly larger than the male (about fifteen cm); the young is uniformly dark.

Many anomalously white coloured individuals have been confirmed, mostly in the North Atlantic, but also notably around Turkish and British coasts, and in the Wadden Sea, Bay of Fundy and around the coast of Cornwall.[7][8][9]

Although conjoined twins are rarely seen in wild mammals, the first known case of a two-headed harbour porpoise was documented in May 2017 when Dutch fishermen in the North Sea caught them by chance.[10] A study published by the online journal of the Natural History Museum Rotterdam points out that conjoined twins in whales and dolphins are extremely rare.[11]

Taxonomy

The English word porpoise comes from the French pourpois (Old French porpais, 12th century), which is from Medieval Latin porcopiscus, which is a compound of porcus (pig) and piscus (fish). The old word is probably a loan-translation of a Germanic word, compare Danish marsvin and Middle Dutch mereswijn (sea swine). Classical Latin had a similar name, porculus marinus. The species’ taxonomic name, Phocoena phocoena, is the Latinized form of the Greek φώκαινα, phōkaina, “big seal”, as described by Aristotle; this from φώκη, phōkē, “seal“.

The species is sometimes known as the common porpoise in texts originating in the United Kingdom. In parts of Atlantic Canada it is known colloquially as the puffing pig, and in Norway ‘nise’, derived from an Old Norse word for sneeze; both of which refer to the sound made when porpoises surface to breathe.

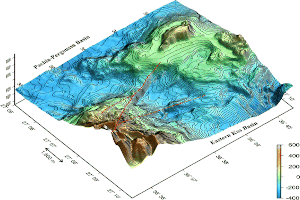

Distribution

Biotope

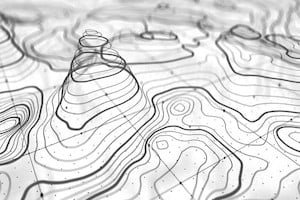

The harbor porpoise frequents cold coastal waters (temperature below 16 ° C) but also estuaries and ports. It even goes up in the great rivers. It can descend to a depth of 200 m.

The harbour porpoise species is widespread in cooler coastal waters of the North Atlantic, North Pacific and the Black Sea.[12] The populations in these regions are not continuous[13] and are classified as separate subspecies with P. p. phocoena in the North Atlantic and West Africa, P. p. relicta in the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, an unnamed population in the northwest Pacific and P. p. vomerina in the northeast Pacific.[6][12] Recent genetic evidence suggests the harbour porpoise population structure may be more complex, and that they should be reclassified.[14]

In the Atlantic, harbour porpoises may be present in a curved band of water running from the coast of West Africa to the coasts of Spain, France, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Scandinavia, Iceland, Greenland, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and the eastern seaboard of the United States.[13][12] The population in the Baltic Sea is limited in winter due to sea freezing, and is most common in the southwest parts of the sea. There is another band in the Pacific Ocean running from the Sea of Japan, Vladivostok, the Bering Strait, Alaska, British Columbia, and California.[13][12]

Population Status

The harbour porpoise has a global population of at least 700,000.[12] In 2016, a comprehensive survey of the Atlantic region in Europe, from Gibraltar to Vestfjorden in Norway, found that the population was about 467,000 harbour porpoises, making it the most abundant cetacean in the region, together with the common dolphin.[15] Based on surveys in 1994, 2005 and 2016, the harbour porpoise population in this region is stable.[15] The highest densities are in the southwestern North Sea and oceans of mainland Denmark;[15] the latter region alone is home to about 107,000 harbour porpoises.[16] The entire North Sea population is about 335,000.[17] In the Western Atlantic it is estimated that there are about 33,000 harbour porpoises along the mid-southwestern coast of Greenland (where increasing temperatures have aided them),[12] 75,000 between the Gulf of Maine and Gulf of St. Lawrence, and 27,000 in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.[3] The Pacific population off mainland United States is about 73,000 and off Alaska 89,000.[3] After sharp declines in the 20th century, populations have rebounded in the inland waters of Washington state.[18] In contrast, some subpopulations are seriously threatened. For example, there are less than 12,000 in the Black Sea,[3] and only about 500 remaining in the Baltic Sea proper, representing a sharp decrease since the mid-1900s.[19]

Ecology

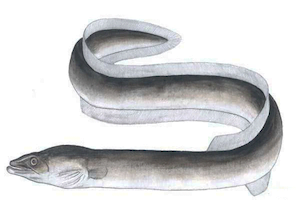

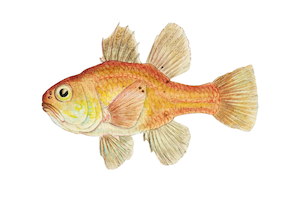

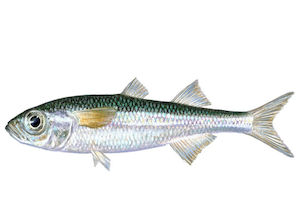

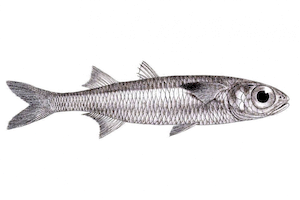

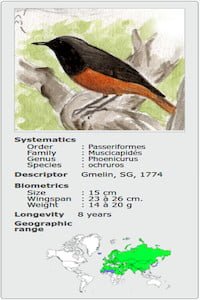

Harbour porpoises prefer temperate and subarctic waters.[13] They inhabit fjords, bays, estuaries and harbours, hence their name.[13] They feed mostly on small pelagic schooling fish, particularly herring, capelin, and sprat.[12] They will, however, eat squid and crustaceans in certain places.[12] This species tends to feed close to the sea bottom, at least for waters less than 200 m (660 ft) deep.[12] However, when hunting sprat, porpoise may stay closer to the surface.[12] When in deeper waters, porpoises may forage for mid-water fish, such as pearlsides.[12] A study published in 2016 showed that porpoises off the coast of Denmark were hunting 200 fish per hour during the day and up to 550 per hour at night, catching 90% of the fish they targeted.[20][21] Almost all the fish they ate were very small, between 3 and 10 cm (1.2–3.9 in) long.[20][21]

Harbour porpoises tend to be solitary foragers, but they do sometimes hunt in packs and herd fish together.[12] Young porpoises need to consume about 7% to 8% of their body weight each day to survive, which is approximately 15 pounds or 7 kilograms of fish. Significant predators of harbour porpoises include white sharks and killer whales (orcas). Researchers at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland have also discovered that the local bottlenose dolphins attack and kill harbour porpoises without eating them due to competition for a decreasing food supply.[22] An alternative explanation is that the adult dolphins exhibit infanticidal behaviour and mistake the porpoises for juvenile dolphins which they are believed to kill.[23] Grey seals are also known to attack harbour porpoises by biting off chunks of fat as a high energy source.[24]

Alimentation

The harbor porpoise is an odontocete, that is to say a toothed cetacean: it feeds on fish (herring and mackerel in particular, but also sardines, sole, hake, etc.), cephalopods and small crustaceans that it hunting near the bottom. He is then agile and gluttonous.

Reproduction

In this porpoise, sexual maturity is reached between three and six years, depending on sex and geographic area. Females have a baby every year or every two years, depending on the sector, and therefore four to eight during their life.

In Europe, matings take place in summer. After a gestation period of ten to eleven months, the births take place between May and August.

A baby at birth measures approximately 75 cm and weighs approximately 5 kg. It then swims spontaneously towards the surface and breathes. Weaning lasts between four and eight months. Milk is rich in fat and protein. The little ones get bigger quickly. Their teeth appear with the first catches of fish. Complete independence is acquired around one year.

The male porpoise holds the cetacean record for the ratio of total weight to testis weight (equivalent to that of a whale) to allow repeated ejaculations at short intervals.

Calves are weaned after 8–12 months.[13] Their average life-span is 8–13 years, although individuals have reached 20.[12][26] In a study of 239 dead harbour porpoises in the Gulf of Maine–Bay of Fundy, the vast majority were less than 12 years old and the oldest was 17.[27]

Behaviour and Life-span

Some studies suggest porpoises are relatively sedentary and usually do not leave a certain area for long.[12] Nevertheless, they have been recorded to move from onshore to offshore waters along coast.[12] Dives of 220 m (720 ft) by harbour porpoises have been recorded.[12] Dives can last five minutes but typically last one minute.[25]

The social life of harbour porpoises is not well understood. They are generally seen as a solitary species.[13] Most of the time, porpoises are either alone or in groups of no more than five animals.[13] [12]

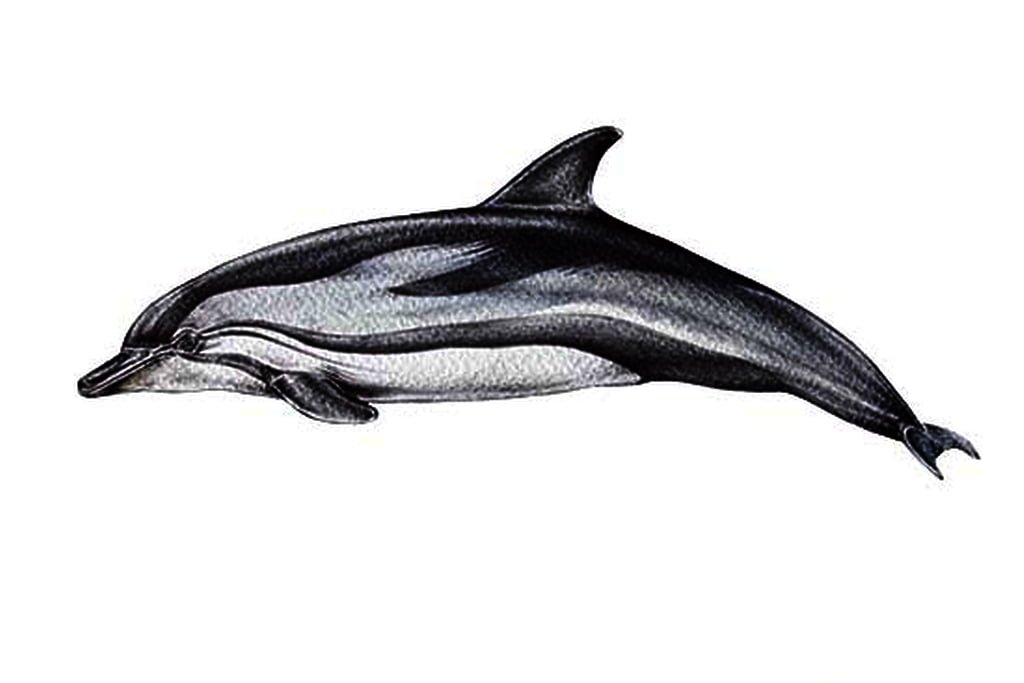

Similar Species

There are three other species in the Phocoenidae family:

– Phocoena spinipinnis , the Burmeister porpoise lives in the coastal areas and estuaries of South America.

– Phocoena dioptrica , the Spectacled Porpoise lives in the Antarctic zone. It is the largest of the porpoises. His eyes are circled in white.

– Phocoena sinus , the California porpoise lives in the Gulf of California and the Colorado Delta. Her eyes and mouth are outlined in black.

Phocoenoides dalli , Dall’s porpoise, is black and white. Its fin is in the shape of a “comma”. It is only present in the North Pacific.

When the size of the animal is not well understood, the fin of the pointed-snout whale ( Balaenoptera acutorostrata ) is very similar.

Associated Life

Porpoises can be parasitized by lampreys or worms. The affected areas are the bronchi, the lungs and the cardiovascular system. These parasites can also make the animal deaf.

The porpoise’s predators are the great sharks ( Greenland shark and white shark ) and orcas . They are also attacked by certain dolphins (bottlenose dolphin and common dolphin ) who no longer consider it as food but as competition against prey.

Various Life

Being a coastal species, and therefore that can be observed quite easily, the harbor porpoise was the basis, along with the bottlenose dolphin, of the first research on cetaceans.

The porpoise has a wide sound spectrum (0 to 160 kHz), for communication as well as for echolocation *.

He lives in small groups (from 2 to 8) or in couple (mother / young) or even solitary. Often, mature females form isolated groups.

The longevity of this porpoise is 10 to 15 years, with a reported record of 24 years.

Three subspecies have been described:

Phocoena phocoena phocoena (Linnaeus, 1758): the North Atlantic porpoise

Phocoena phocoena relicta Abel, 1905: the Black Sea porpoise

Phocoena phocoena vomerinaGill, 1865: the porpoise of the North Pacific.

Of the geographic subspecies of the porpoise, the Black Sea one is the smallest and has adapted to lower salinity. In the Atlantic, porpoises in the west are larger than those in the east. Finally, the Baltic porpoises are the darkest. These different populations do not mix.

Threats

Hunting

Harbour porpoises were traditionally hunted for food, as well as for their blubber, which was used for lighting fuel. Among others, hunting occurred in the Black Sea, off Normandy, in the Bay of Biscay, off Flanders, in the Little Belt strait, off Iceland, western Norway, in Puget Sound, Bay of Fundy and Gulf of Saint Lawrence.[3][28][29] The drive hunt in the Little Belt strait is the best documented example. Thousands of porpoises were caught there until the end of the 19th century, and again in smaller scale during the world wars.[30] Currently, however, this species is not subject to commercial hunting, but it is hunted for food and sold locally in Greenland.[3] In prehistoric times, this animal was hunted by the Alby People of the east coast of Öland, Sweden.

Interactions with Fisheries

A harbour porpoise in captivity in Denmark. The individuals at the center were rescued[31] after being injured following entanglement in fishing gear, showing the danger nets can represent to the species[32]

The main threat to porpoises is static fishing techniques such as gill and tangle nets. Bycatch in bottom-set gill nets is considered the main anthropogenic mortality factor for harbour porpoises worldwide. Several thousand die each year in incidental bycatch, which has been reported from the Black Sea, the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, off California, and along the east coast of the United States and Canada.[3] Bottom-set gill nets are anchored to the sea floor and are up to 12.5 miles (20 km) in length. It is unknown why porpoises become entangled in gill nets, since several studies indicate they are able to detect these nets using their echolocation.[33][34] Porpoise-scaring devices, so-called pingers, have been developed to keep porpoises out of nets and numerous studies have demonstrated they are very effective at reducing entanglement.[35][36] However, concern has been raised over the noise pollution created by the pingers and whether their efficiency will diminish over time due to porpoises habituating to the sounds.[32][37]

Mortality resulting from trawling bycatch seems to be less of an issue, probably because porpoises are not inclined to feed inside trawls, as dolphins are known to do.

Overfishing

Overfishing may reduce preferred prey availability for porpoises. Overfishing resulting in the collapse of herring in the North Sea caused porpoises to hunt for other prey species.[38] Reduction of prey may result from climate change, or overfishing, or both.

Noise Pollution

Noise from ship traffic and oil platforms is thought to affect the distribution of toothed whales, like the harbour porpoise, that use echolocation for communication and prey detection. The construction of thousands of offshore wind turbines, planned in different areas of North Sea, is known to cause displacement of porpoises from the construction site,[39] particularly if steel monopile foundations are installed by percussive piling, where reactions can occur at distances of more than 20 km (12 mi).[40] Noise levels from operating wind turbines are low and unlikely to affect porpoises, even at close range.[41][42]

Pollution

Marine top predators like porpoises and seals accumulate pollutants such as heavy metals, PCBs and pesticides in their fat tissue. Porpoises have a coastal distribution that potentially brings them close to sources of pollution. Porpoises may not experience any toxic effects until they draw on their fat reserves, such as in periods of food shortage, migration or reproduction.

Climate Change

An increase in the temperature of the sea water is likely to affect the distribution of porpoises and their prey, but has not been shown to occur. Reduced stocks of sand eel along the east coast of Scotland, a pattern linked to climate change, appears to be the main reason for the increase in malnutrition in porpoises in the area.[43]

Conservation Status

Overall, the harbour porpoise is not considered threatened and the total population is in the hundreds of thousands.[3]

The harbour porpoise populations of the North Sea, Baltic Sea, western North Atlantic, Black Sea and North West Africa are protected under Appendix II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS).[44] In 2013, the two Baltic Sea subpopulations were listed as vulnerable and critically endangered respectively by HELCOM.[45] Although the species overall is considered to be of Least Concern by the IUCN,[3] they consider the Baltic Sea and Western African populations critically endangered, and the subspecies P. p. relicta of the Black Sea endangered.[46][47][48]

In addition, the harbour porpoise is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS), the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS) and the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU).

Further Information

It is a fierce animal. It swims very rarely on the bow, but it can rest for a long time on the surface in calm weather. Jumps are rare. It probes for three minutes on average, then stays on the surface for about a minute. When he is hunting, his breathing rate is 4 breaths every fortnight. En route, he can breathe up to 8 times with an interval of one minute.

Unlike some dolphins, the porpoise does not adapt to life in captivity and its maximum life expectancy is then two to three years.

The main threat to the porpoise is pollution of the oceans, the most toxic being that linked to heavy metals. Accidental catches in the nets are not negligible either.

In recent years, porpoises have been seen in certain rivers in northern Germany. They had previously disappeared due to pollution. On the other hand, there are still a century, one could see porpoises which went up the Seine to Paris. This has not happened since.

An inhabitant of the Belgian coast relates, in March 2013 (in Niewpoort and in La Panne):

directional emission of their ultrasound would focus towards the sand to locate and capture the small fish while making them “blind” to the surrounding nets in which they would then get stuck … They would be swaddled in the bottom net, because of this detection posture directed only towards the bottom, without any other effective “vision”, a fortiori in murky waters and / or at night. Nets to which they would then inadvertently remain attached by their pectoral fins, their caudal fins and / or their rostrum, thus moving laterally while prospecting, carried by the tidal current. Ending irreparably by drowning while struggling to disentangle themselves, even if most of the time they would detach themselves from it but already dead, due to the repeated shaking of the waves and / or the swell … “

In 2012, an international study reconstructed the history of Black Sea porpoises through genetics. In this way, the authors show a strong growth of this population during the reconnection of the Black Sea – Mediterranean. Much more recently, this same population has seen its numbers reduced by 90% in 50 years, which coincides with the hunting of small cetaceans authorized until 1983. At the same time as the overexploitation of fish stocks, this predator hunt has triggered disturbances in the structure of the local ecosystem (toxic algae, stock crash, …).