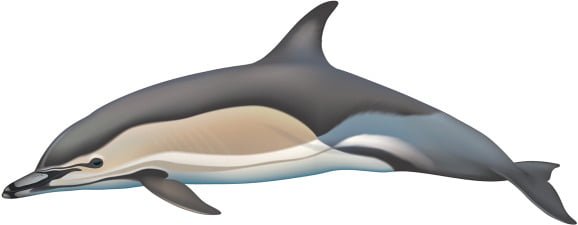

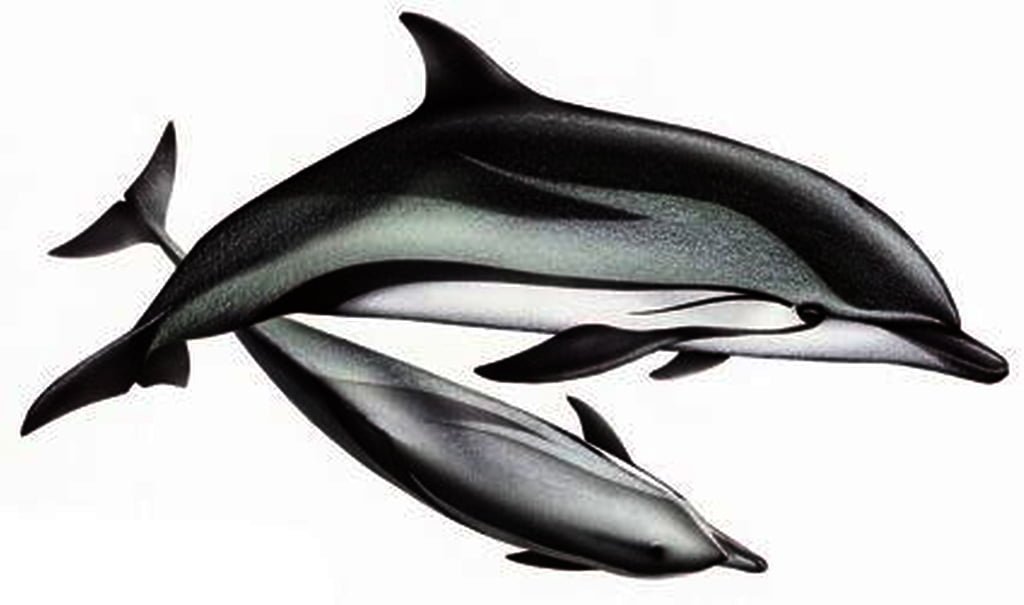

Stenella Coeruleoalba

– Striped Dolphin –

| Conservation status |

|---|

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)[2] |

| Scientific classification |

Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833)

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Delphinidae |

| Genus: | Stenella |

| Species: | S. coeruleoalba |

The striped dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba) is an extensively studied dolphin found in temperate and tropical waters of all the world’s oceans. It is a member of the oceanic dolphin family, Delphinidae.

Description

The striped dolphin has a similar size and shape to several other dolphins that inhabit the waters it does (see pantropical spotted dolphin, Atlantic spotted dolphin, Clymene dolphin). However, its colouring is very different and makes it relatively easy to notice at sea. The underside is blue, white, or pink. One or two black bands circle the eyes, and then run across the back, to the flipper. These bands widen to the width of the flipper which are the same size. Two further black stripes run from behind the ear — one is short and ends just above the flipper. The other is longer and thickens along the flanks until it curves down under the belly just prior to the tail stock. Above these stripes, the dolphin’s flanks are coloured light blue or grey. All appendages are black, as well. At birth, individuals weigh about 10 kg (22 lb) and are up to a meter (3 feet) long. By adulthood, they have grown to 2.4 m (8 ft) (females) or 2.6 m (8.5 ft) (males) and weigh 150 kg (330 lb) (female) or 160 kg (352 lb) (male). Research suggested sexual maturity was reached at 12 years in Mediterranean females and in the Pacific at between seven and 9 years. Longevity is about 55–60 years. Gestation lasts about 12 months, with a three- or four-year gap between calving.

In common with other dolphins in its genus, the striped dolphin moves in large groups — usually up to thousands of individuals in number. Groups may be smaller in the Mediterranean and Atlantic. They may also mix with common dolphins. The striped dolphin is as capable as any dolphin at performing acrobatics — frequently breaching and jumping far above the surface of the water. Sometimes, it approaches boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, but this is dramatically less common in other areas, particularly in the Pacific, where it has been heavily exploited in the past. Striped dolphins are known as “streakers” throughout the eastern tropical Pacific due to their behavior of rapidly swimming away from vessels to avoid collisions[citation needed]

The blue and white dolphin can be recognized by its slender silhouette and the characteristic design that adorns its sides: a thin black line stretches from the eye towards the anal region while the white covering its sides rises in a “brushstroke”. or in a clear “flame” towards the ridge.

This dolphin can reach 2.50 m and 150 kg in some parts of its range; in the Mediterranean, the size varies from 1.80 m to 2.20 m for a weight ranging from 65 to 105 kg.

The beak is thinwithout being stretched out, and it is two-tone. It is quite distinct from melon *. The mouth, of straight shape, shoots out towards the eye and is provided with two mandibles which each have 80 to 110 fine teeth, similar, very pointed and slightly curved. The bony palate is flat, unlike that of the common dolphin (useful for identifying stranded animals).

The melon and the back to the caudal fin are dark gray to black. The belly is pure white. Under the surface and by transparency, it can therefore appear in white and blue. Old individuals are recognizable by their whitening on the top of the melon.

Sickle-shaped dorsal fin* measures about twenty centimeters and is located at mid-length. The pectoral fins are proportionately small in size and also slightly sickle-shaped. As for the caudal, its shape is rather concave and well marked by a small median groove.

The blue and white dolphin can also be recognized at sea by its very demonstrative behavior with frequent jumps . He sometimes comes to swim at the bow of boats.

Taxonomy

The striped dolphin is one of five species traditionally included in the genus Stenella; however, recent genetic work by LeDuc et al. (1999) indicates Stenella, as traditionally conceived, is not a natural group. According to that study, the closest relatives of the striped dolphin are the Clymene dolphin, the common dolphins, the Atlantic spotted dolphin, and “Tursiops” aduncus, which was formerly considered a subspecies of the common bottlenose dolphin. The striped dolphin was described by Franz Meyen in 1833.

Distribution

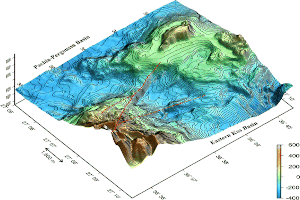

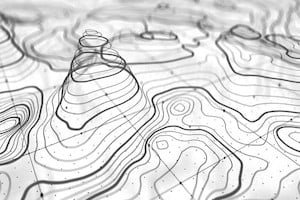

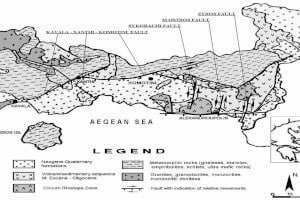

The striped dolphin inhabits temperate or tropical, off-shore waters. It is found in abundance in the North and South Atlantic Oceans, including the Mediterranean (sightings and strandings have been reported rather recently in Sea of Marmara[4]) and Gulf of Mexico, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean. Roughly speaking, it occupies a range running from 40°N to 30°S. It has been found in water temperatures ranging from 10 to 26 °C, though the standard range is 18-22 °C. In the western Pacific, where the species has been extensively studied, a distinctive migration pattern has been identified. This has not been the case in other areas. The dolphin appears to be common in all areas of its range, though that may not be continuous; areas of low population density do exist. The total population is in excess of two million. The southernmost record is of a stranded individual nearby Dunedin, southern New Zealand in 2017.[5]

Biotope

The blue and white dolphin is an offshore animal. It happens to come closer to the coasts to feed but it is generally found beyond the isobath * of 200 m. Its distribution is closely linked to the shifting distribution of schools of small fish and cephalopods on which it feeds.

Alimentation

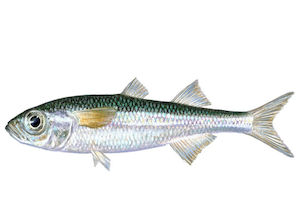

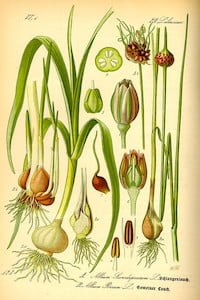

The adult striped dolphin eats fish, squid, octopus, krill, and other crustaceans. Mediterranean striped dolphins seem to prey primarily on cephalopods (50-100% of stomach contents), while northeastern Atlantic striped dolphins most often prey on fish, frequently cod. They mainly feed on cephalopods, crustaceans, and bony fishes. They feed anywhere within the water column where prey is concentrated, and they can dive to depths of 700 m to hunt deeper-dwelling species.

The diet consists mainly of fish, cephalopods and crustaceans, depending on the resources available because the species is rather opportunistic.

In the Mediterranean, autopsy of stranded dolphins has shown that they feed mainly on cephalopods. Elsewhere, stomach contents revealed that they were feeding (besides crabs and squid) on fourteen species of fish, including cod.

Blue and white dolphins mostly hunt at night and early in the morning. In several points of the Mediterranean coastline, we can see them approaching the coast at night.

Reproduction

The meeting of the partners takes place during the gathering of several groups. Mixed groups are formed. Dolphins are very “tactile” and spend a lot of time cuddling! On the other hand, they are not at all faithful (in the human sense of the term).

With the exception of the presence of mammary slits, visible on either side of the female’s genital slit, there is no morphological difference between male and female (no sexual dimorphism). The male’s invisible penis is housed inside the animal in an abdominal skin fold called the penile slit and held by two retractor muscles. He does not need an influx of blood to achieve an erection, as this penis is fibro-elastic in texture. The female’s slit encloses a pre-vaginal clitoris.

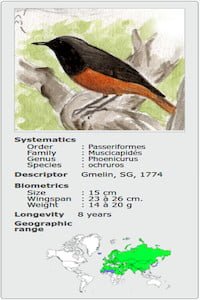

Sexual maturity occurs at 8 years for females and between 9 and 10 years for males.

Known breeding periods are January-February, May-June and September-October. In the Mediterranean, matings as well as births are mainly observed in summer.

The reproduction periods begin with amorous displays. Very fast jumps and top speeds are part of it but other signs such as biting, whistling, screaming, seeking contact with his chosen one are part of the premarital scenes. The male can even embrace his beautiful, using his two pectorals …

If she is consenting, she will take a position allowing the male to introduce his penis. If, on the other hand, she shows signs of reluctance, the males do not hesitate to help each other to satisfy their desire, succeeding each other, in turn, to allow forced coitus (rapes?).

Dolphins are viviparous * placental mammals. Gestation lasts 12 months and a female can give birth every 2 or 3 years. She will give birth to only one dolphin, twins being rather rare, but possible.

Parturition * naturally takes place in water. During this birth, under the effect of uterine contractions of the mother, the dolphin comes by the tail in order to delay as late as possible the contact of its airways with water and thus avoid drowning. The umbilical cord is severed automatically, separating the newborn from its mother. The risk of drowning is indeed important because the lungs of this one do not yet contain air.

As with all dolphins, the mother can be assisted during childbirth by another female. Commonly called “the aunt”, she will take charge of the newborn and lead him to the surface so that he can take his first breath.

The young are around 90 cm tall at birth and often weigh less than 10 kg. As soon as it is born, the dolphin will have to suckle its mother. The nipples are located around the mother’s sex and the mammary muscle, on stimulation of the latter, allows the milk to be sent directly into the mouth of her baby.

The dolphin will only be weaned after 18 months.

During this whole period, his mother taught him the art of hunting.

When there are newborns, the whole group takes care of them and becomes more suspicious of the boats in order to protect the little ones.

There is a significant peak in mortality when the juveniles are weaned.

Associated Life

Stenella coeruleoalba sometimes mixes with other cetacean species ( Delphinus delphis or Grampus griseus , for example).

It is also found with certain species of tuna (yellowfin tuna, for example), whose movements it follows.

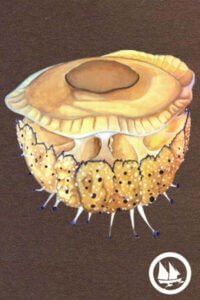

Parasitism :

About 25 species of parasites have been identified in our stenelle, most often internal parasites. It also seems to occasionally harbor a host named Anisakis typica (Diesing, 1860), a nematode which causes lesions in the digestive tract. These lesions are rarely liable to cause death but contribute to weakening populations.

Various Biology

The species shows 72 to 98 conical teeth on the upper jaw and 78 to 110 on the lower jaw.

The teeth are similar in shape.

Dive time can be up to 15 minutes and the maximum estimated depth is 200 meters.

When moving, a third of the group is always out of the water during swimming movements.

Its speed can reach 35 km / h with peaks of 60 km / h!

In the wild, blue and white dolphins can live up to 40-45 years. If the average is 35 years, the known record would be 57 years.

Stenella coeruleoalbais a rather nocturnal and organized predator. Dispersing in small groups of 1 to 3 individuals, the whole group is able to cover a perimeter of around ten square kilometers. The echolocation function is then essential to carry out the search for food. In the early morning, after gathering, the group allows itself phases of rest alternating during the day with social activities, playful phases … interspersed with sessions of predation essential to the necessary daily nutritional intake.

The daytime hunting technique turns out to be different and more tactical. The group remains united and uses a method of grouping prey using jumps, rapid movements, circling, forcing the school to tighten,

Color variations exist. The blue and white skin color can vary in brown and ocher, the Anglo-Saxons and the Portuguese therefore name this dolphin “striped dolphin”, thinking this name more appropriate. Likewise, in the Mediterranean, variations in the color of the white ventral part, which have become pink, have been observed.

We can meet the blue and white dolphin in groups of 10 to 100 individuals up to several hundred and even (rarely) up to 3,000 individuals!

It is sometimes associated with other species such as the common dolphin and the Risso’s dolphin , or even the fin whale .

Sound emissions :

Echolocation * is a technique used by cetaceans, like natural sonar. It is a so-called “pulse” sound. The dolphin sends sound emissions from its melon to the target (fish, congener, man) which will bounce off the obstacle and return to the cetacean in the form of echoes. The lower jaw of the animal will pick up its signals, transmit them to the brain which, after detailed analysis, will translate the characteristics of the echo by composing a precise acoustic image of the environment and the target.

Sound emissions of different frequencies (so-called “continuous modulated” sounds) also serve as language. In order to communicate with each other, they emit “clicks”, “whistles”, “cackles”…. At least six categories of sounds have been identified, with clicks and hissing variations of various frequencies. So far, four categories seem to have been identified as:

Breathing :

The dolphin’s breathing is voluntary and is carried out by means of a vent * 3 to 4 cm in diameter. It thus muscularly controls its opening or closing. The position of this one at the top of the melon, allows him to be able to go up to breathe on the surface without stopping his swimming. This voluntary and non-reflex breathing causes the animal to involve each cerebral hemisphere alternately when sleeping.

Vision :

Dolphins see both underwater and out of the water thanks to a feature of the lens of the eye which deforms slightly when passing from the aquatic environment to the air environment.

Similar Species

Delphinus delphis : the common dolphin, of very similar size and silhouette, is distinguished by the coloring of its sides adorned with a semi-circular spot of sand color, followed by another, light gray, forming with the first a horizontal hourglass drawing. You can also spot the V-shape drawn by the dark part of the back directly above the dorsal fin.

Stenella longirostris : the long-beaked dolphin having roughly the same distribution as S. coeruleoalba , is distinguished by its distinctly longer beak, its high, triangular dorsal fin and the absence of “flame” on the tricolor flanks ( black, gray and white). This species is absent from French coasts, including the Mediterranean.

Stenella clymene: the Clymene’s dolphin only has the tropical Atlantic as a common territory with S. coeruleoalba . It is approximately the same size. But its sides do not bear the flamed design of the blue and white dolphin. It is dark gray on the back, white on the belly, and a wavy pale gray stripe running in between. The tip and the lips are black, like the fins.

Conservation

The eastern tropical Pacific and Mediterranean populations of the striped dolphin are listed on Appendix II [6] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS), since they have an unfavorable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organized by tailored agreements.[7]

On the IUCN Red List the striped dolphin classifies as vulnerable due to a 30% reduction in its subpopulation over the last three generations. These dolphins may also be an indicator species for long term monitoring of heavy metal accumulation in the marine environment because of its importance in the Japan pelagic food web as well as its ability to live for many years.

In addition, the striped dolphin is covered by the Agreement on the Conservation of Small Cetaceans of the Baltic, North East Atlantic, Irish and North Seas (ASCOBANS),[8] the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans in the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and Contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS),[9] the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU)[10] and the Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Conservation of the Manatee and Small Cetaceans of Western Africa and Macaronesia (Western African Aquatic Mammals MoU)

Conservation efforts have included having ship lines take a new path to their destination such as cruise lines as well as reduced human interaction close up. Feeding the dolphins has also become a problem, and has led to behavioral changes. This has also been suggested as another reason for mortality events.

Human interaction

Japanese whalers have hunted striped dolphins in the western Pacific since at least the 1940s. In the heyday of “striped dolphin drives”, at least 8,000 to 9,000 individuals were killed each year, and in one exceptional year, 21,000 individuals were killed. Since the 1980s, following the introduction of quotas, this number has fallen to around 1,000 kills per year. Conservationists are concerned about the Mediterranean population which is threatened by pollution, disease, busy shipping lanes, and heavy incidental catches in fishing nets such as long-liners, trawlers, gill nets, trammel and purse seine nets. . Recent threats include military sonar, and chemical pollution from near by harbors. Hydrocarbons are also a major concern such has PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and HCB (hexachlorobenzene). These are said to give problems to additional food chains as well as doing a full body test to see what hydrocarbons may be passed down through parturition and lactation. Attempts have been made to keep the striped dolphin in captivity, but most have failed, with the exception of a few captured in Japan for the Taiji Whale Museum.

Striped dolphins are one of the targeted species in the Taiji dolphin drive hunt.

Strandings and Mortality

The striped dolphin once thrived, numbering 117,880 before 1990. Since then, the population has suffered from incidental catches in fisheries. Mortality has been considered unsustainable, but there is a lack of data which hampers conservation efforts.

Various cases of stranding over the years have been a cause for alarm. With an unfavorable conservation status and the increasing amount of debris piling in the ocean every year, striped dolphin’s population is decreasing. 37 dolphins stranded off the Spanish Mediterranean coast were suffering from dolphin morbillivirus (DMV). The causes of these stranding have been changing from epizootic to enzootic.

Cetacean morbillivirus (CeMV) can be divided into six strains in cetaceans throughout the world, causing widespread mortality events in Europe, North America, and Australia. Studies have indicated that characteristics of CeMV may be more closely associated with disease in ruminants than carnivore species, which is representative of their evolutionary histories. Common disease presentation includes broncointerstitial pneumonia, encephalitis, lymphocytopenia, and increases in multinucleated cells. CeVM causes immunosuppression, increasing risk to secondary infection following acute resolution of clinical signs. Hypothesized transmission routes include via aerosol and trans-placentally.

The unusual mortality events (UMEs) among striped dolphins suggest that parasitic diseases may be increasing in the open ocean due to anthropogenic causes. In addition, case reports indicate nematodes present in the brain of the striped dolphin, described as a single round and thin worm with numerous eggs in the subcortical lesions, including the optic nerve. It is hypothesized this worm belongs to the genus Contracaecum, the same genus which has been reported to infect the brains of sea lions. Caution should be employed when handling these animals due to the possibility of a serious injury if the right steps are not taken in order to ensure both human and animal safety.

Further Information

The speed of the animal (35 km / h – peaks at 60) allows it to swim at the bow of fast ships. However, it happens that animals are injured by propellers or that young are separated from their mother because of the behavior of some boaters disrespectful.

It is indeed a species easy to observe at sea. If the conditions are good, the animals come themselves to swim against the hull of the ship for the happiness of the occupants. In this case, it is best to maintain the course and the speed at which the animals adapt.

Undoubtedly, they prefer sailboats … There is now a code of conduct in the Mediterranean which recommends respecting a vigilance zone of 300 m around animals and not trying to follow them, let alone swim with them. In any case, they are much more fierce than bottlenose dolphins. If you see them, let them decide on the meeting …

Stenella coeruleoalba does not support captivity, refusing any form of training.

In addition, the species is struck there by certain infections which are unknown to it in the wild.

In 2008, the Corso-Liguro-Provençal population (Pelagos sanctuary) of the blue and white dolphin was estimated at around 35,000 individuals and at 300,000 for the entire Mediterranean. The abundance of this population has earned it the nickname “Mediterranean sparrows”.

Although still numerous, they are victims of various threats: certain fishing nets, pollution, lack of food (overfishing), acoustic disturbances (boats, military activities, seismic explorations, etc.), etc.

Driftnets, due to the number of accidental captures of dolphins (around 300 per year in the Pelagos sanctuary) have been banned since 2002 on the French Mediterranean coasts. But this ban has only really been applied since 2008, after several years of exemptions and tests of acoustic repellents.

In October 1992, a blue and white dolphin was found on a beach in Tadoussac, Quebec, on the Saint-Laurent! It is well north of the range of Stenella coeruleoalba and it was therefore an exceptional find that this species in the St. Lawrence! Scientists believe this blue-and-white dolphin mingled with a group of white- sided dolphins Lagenorhynchus acutus, accustomed to these latitudes and following their usual path in this same period.

In 1990, an epidemic killed thousands of blue and white dolphins. The scientists’ hypothesis is that of contamination by DMV, a morbilivirus * (pathology derived from canine distemper and transmitted by fish ingested by mammals) leading to kinds of pneumonia, hemorrhages, diarrhea, respiratory genes … The tissues of the animals autopsied during the strandings showed very high concentrations of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) and heavy metals (these pollutants are indicative of the pollution levels affecting in particular the Mediterranean where the species is very abundant) . The animals were also very weak. These pollutants could have favored the epidemic by an effect on the immune system of dolphins. Otherwise, the lack of food could also be to blame. In 2008 there was an increase in strandings.

It is very rare for animals to run aground alive. During illnesses or intense states of fragility, they move closer to the coast in order to bathe in calmer waters, maintaining the surface then becoming difficult for the weakest. At the end of their strength, they sink and drown or else stranding becomes inevitable!

A network of observers (Echouage Network) is then responsible for intervening for care or for carrying out autopsies or samples from dead animals. Autopsies are a valuable way to better understand the causes of mortality, in order to protect this endearing species.

What to do if a stranded animal is found ?

It is essential to inform the competent authorities (fire brigade, police, gendarmerie) in order to adopt a correct attitude according to the state of health of the animal; the ideal being to prevent theCRMM(Center for Research on Marine Mammals), available seven days a week, at 05.46.44.99.10. This one will take care of forwarding the call to its contact of the closest network.

Then:

– Either the animal is still alive and it is urgent to act according to a particular protocol of which only specialists know the good progress, whether it is for a possible release in the water, for the administration of care of emergencies, or even evacuation to an appropriate center. Our intervention will therefore be limited to its hydration by covering the body with damp cloths, taking care not to obstruct the vent and to ensure the tranquility of the animal which must under no circumstances be moved in order to

– Either the animal is dead and any transport or sampling intervention is prohibited. It would also be dangerous to handle it if it were to be affected by contagious diseases.